Sedimentary Structures

STRATIFICATION refers to the way sediment

layers are stacked over each other, and can occur on the scale of hundreds of meters, and

down to submillimeter scale. It is a fundamental feature of sedimentary rocks.

This picture from Canyonlands National Monument/Utah shows strata

exposed by the downcutting of the Green River. Large scale

stratification as seen here is often the result of the migration of

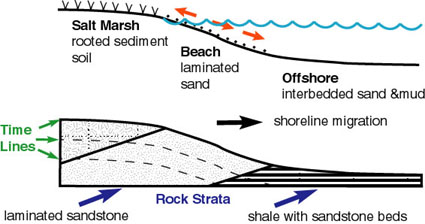

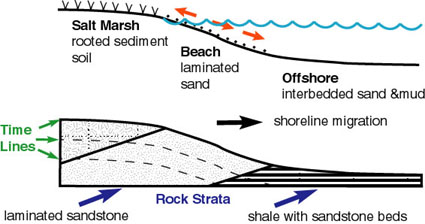

sedimentary environments (see below). Let us imagine a shoreline

that has coexisting slat marsh, beach, and offshore muds. Each

environment is characterized by a different sediment type. If this

shoreline receives more sediment than the waves can remove, it will

gradually build out (to right). Over time the different sediment types

will be stacked on top of each other and the migration of the shoreline

will produce superimposed layers (stratification) of different types of

sedimentary rock. |

|

|

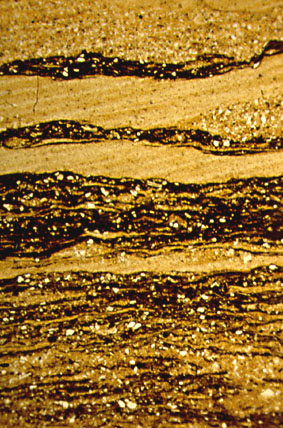

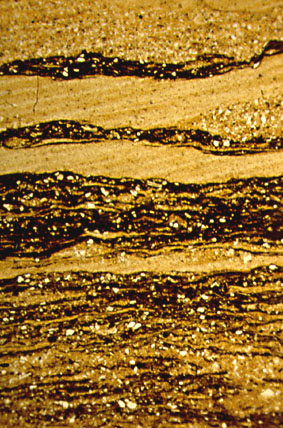

Above image shows small scale stratification

in a shale (image is 7 mm tall). This kind of

stratification is due to alternately operating

depositional processes in the same

environment. Dark layers are rich in organic

matter and are remains of algal mats. Light

layers were deposited by storms or floods,

and briefly interrupted algal growth. |

CROSS-BEDDING is a feature that occurs

at various scales, and is observed in conglomerates and sandstones. It reflects the

transport of gravel and sand by currents that flow over the sediment surface (e.g. in a

river channel). sand in river channels or coastal environments

|

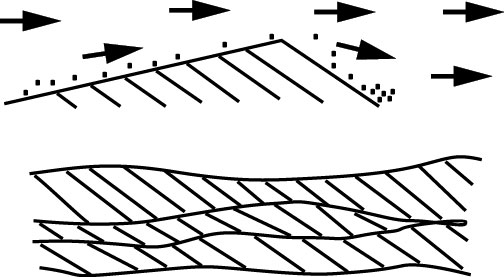

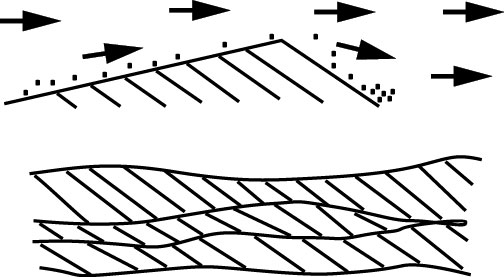

When cross-bedding forms, sand is transported as sand-dune like bodies (sandwave), in

which sediment is moved up and eroded along a gentle upcurrent slope, and redeposited

(avalanching) on the downcurrent slope (see upper half of picture at left). After

several of these bedforms have migrated over an area, and if there is more sediment

deposited than eroded, there will be a buildup of cross-bedded sandstone layers. The

inclination of the cross-beds indicates the transport direction and the current flow (from

left to right in our diagram). The style and size of cross bedding can be used to

estimate current velocity, and orientation of cross-beds allows determination direction of

paleoflow. |

|

Cross-bedding in a sandstone that was originally deposited by rivers. The

deposition currents were flowing from right to left. |

|

Cross-bedding can also be produced when wind blows over a sand surface and creates

sand dunes. The picture on the left shows ancient sanddunes with cross-bedding. |

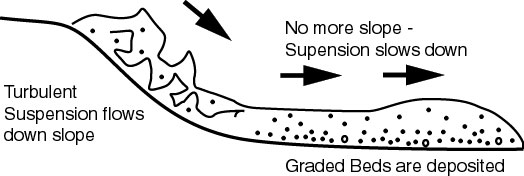

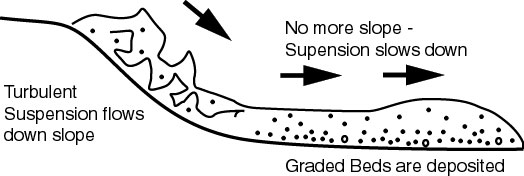

GRADED BEDDING means that the grain size

within a bed decreases upwards. This type of bedding is commonly associated with so called

turbidity currents. Turbidity currents originate on the the slope between continental

shelves and deep sea basins. They are initiated by slope failure (see diagram below),

after sediment buildup has steepened the slope for a while, often some high energy event

(earthquake) triggers downslope movement of sediment. As this submarine landslide picks up

speed the moving sediment mixes with water, and forms eventually a turbid layer of water

of higher density (suspended sediment) that accelerates downslope (may pick up more

sediment). When the flow reaches the deep sea basin/deep sea plain, the acceleration by

gravity stops, and the flow decelerates. As it slows down the coarsest grains settle out

first, then the next finer ones, etc. Finally a graded bed is formed. However,

decelerating flow and graded bedding are no unique feature of deep sea sediments (fluvial

sediments -- floods; storm deposits on continental shelves), but in those other instances

the association of the graded beds with other sediments is markedly different (mud-cracks

in fluvial sediments, wave ripples in shelf deposits).

|

Diagram illustrating the formation of a graded bed (turbidite). Slope failure

produces turbulent suspension that moves/accelerates downslope. Once it reaches the

flat deep sea regions, it slows down due to friction, and gradually the sediment settles

out of suspension. Larger grain sizes settle out first, and then successively

smaller ones. |

|

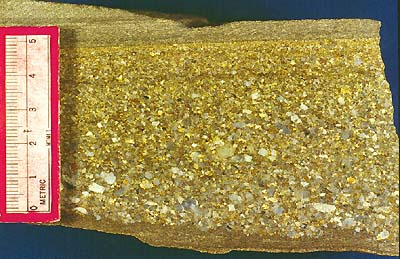

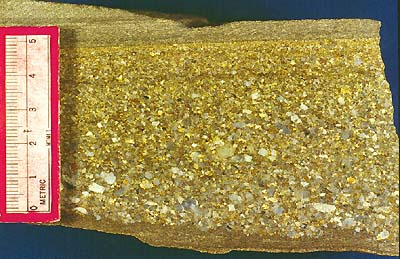

Example of a graded bed. Largest grains occur at the base, and the grain size

gradually decreases. |

RIPPLE MARKS are produced by flowing water or

wave action, analogous to cross-bedding (see above), only on a smaller scale (individual

layers are at most a few cm thick).

|

Current ripples in a creek in Arlington. Ripples are asymmetrical and have a

gentle slop on the right and a steep slope on the left. Comparing with the

explanation of cross-bedding from above, it is obvious that the currents were

flowing from right to left. |

|

Side-view of current rippled sandstone (note coin for scale). The cross-beds or

(more accurately) cross-laminae are inclined to the right, thus the water was flowing from

left to right. |

|

Modern wave ripples in Lake Whitney. Note that ripples are symmetrical, and that

they can branch in a "tuning-fork" fashion. Both features are

characteristic of wave ripples. |

|

Ancient ripples on a sandstone surface. Ripples are symmetrical and show

"tuning-fork" branches. This indicates to a geologist that the sandstones

were deposited in an environment with wave action (nearshore). |

MUD CRACKS form when a water rich mud dries out on

the air.

|

You all have seen this when the mud in a puddle dries out in the days following a

rainstorm. This example is from a construction pit in Arlington. Due to

stretching in all directions, the mudcracks form a polygonal pattern. We also see

several successive generations of cracks. |

|

An example for ancient mudcracks from rocks that are over 1 billion years old

(Snowslip Formation, Montana). Same crack pattern as above, and also second and

third generation cracks. |