NASA Press Release, September 26, 2000

FOUNTAINS OF FIRE ILLUMINATE SOLAR MYSTERY

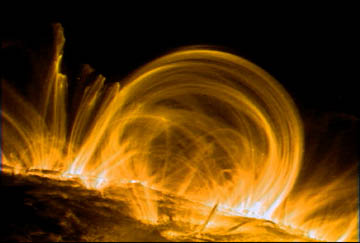

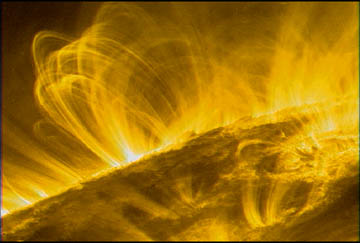

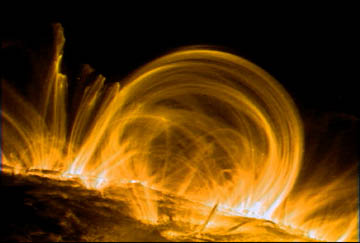

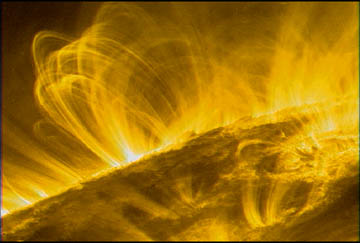

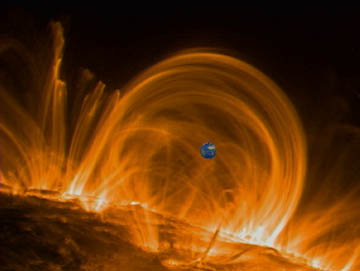

| Giant fountains of fast-moving, multimillion-degree gas in the outermost atmosphere of the Sun have revealed an important clue to a long-standing mystery -- the location of the heating mechanism that makes the corona about 300 times hotter than the Sun's visible surface. |  |

| Scientists discovered an important clue while observing immense coils of hot, electrified gas, known as coronal loops. These

fiery, arching fountains now appear in unprecedented detail with NASA's Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) spacecraft. |

|

Scientists are interested in the corona, which appears as a halo of light seen by the unaided eye during a total solar eclipse,

because eruptive events in this region can disrupt high-technology systems on Earth. Astronomers also hope to use the solar corona

studies to better understand other stars.

"The mysterious energy source that makes the Sun's atmosphere so incredibly hot has been an enigma for more than 70 years, and

before we discover what it is, we needed to learn where it is," said Dr. Markus Aschwanden of the Lockheed-Martin Solar and

Astrophysics Laboratory (LMSAL), in Palo Alto, CA.

Aschwanden is lead author of a paper describing this research to be published in the Astrophysical Journal. "Locating the source of

coronal heating is a key piece of this puzzle, and we are excited that solar observatories like TRACE are allowing us to resolve the

hidden events occurring in the atmospheres of stars."

| The new observations reveal the location of the unidentified energy source, showing that most of the heating occurs low in the

corona, within about 10,000 miles from the Sun's visible surface. The gas fountains form arches, hundreds of thousands of miles

high, capable of surrounding 30 Earths. As gas emerges from the solar surface, it's heated and rises, then cools and crashes back

to the surface at more than 60 miles per second. In the picture at right the Earth is drawn in for scale. |

|

Millions of different-sized coronal loops comprise the corona, and a 30-year-old theory assumes the loops are heated evenly

throughout their height. The TRACE observations show that instead, most of the heating must occur at the base of the loops, near

where they emerge from and return to the solar surface.

The old theory of uniform heating predicted that the loops would be substantially hotter at their tops because gas at the top of

the loops is thinner, and does not radiate heat away as efficiently as the dense gas near the bottom. If the loop were

heated evenly over its entire height, the top, which can't lose heat as well, would become hotter than the rest. Earlier, less-detailed observations of the coronal loops could not confirm nor

invalidate the uniform heating theory because they could not reveal that the loop tops were really about the same temperature

as the bases.

However, the high-resolution TRACE pictures show that, just as a thick piece of rope consists of many thin fibers, what was thought

to be one coronal loop is actually a bundle of thin, individual loops. Although some thin loops in the bundle are hotter than

other spirals, precise measurements by TRACE show that, over its height, each separate, thin loop varies much less than the uniform

heating theory predicts.

Movie clips of TRACE observations: Movie1;

Movie 2; Movie3;

Movie4

"Since a loop loses heat most rapidly from its bases, most of the heat must also be going in at the bases for the loop to be at a

uniform temperature," said Dr. Karel Schrijver, a member of the research team, also of LMSAL. "If this were not so, the lower

parts would have been much cooler than the tops, which do not lose heat as quickly."

NASA Administrator Daniel S. Goldin unveiled the new TRACE images today, along with Ellen Futter, president of the American Museum

of Natural History, at the museum's Rose Center for Earth and Space, New York.

TRACE, launched in April 1998, is training its powerful telescope on the "transition region" of the Sun's atmosphere, a dynamic

region between the relatively cool surface and lower atmosphere regions of the Sun, about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and the

extremely hot upper atmosphere, which burns up to 3 million degrees Fahrenheit.

For images and more information on the Internet, visit:

http://www.gsfc.nasa.gov/GSFC/SpaceSci/sunearth/tracecl.htm